ASTANA – Kazakhstan is commemorating the 130th anniversary of Ilyas Zhansugurov, a distinguished Kazakh poet, writer, and the first chairman of the Union of Writers of Kazakhstan. Zhansugurov made significant contributions to the development of the national poetic culture, innovatively enriching Kazakh oral folk art traditions.

Photo credit: egemen.kz

Zhansugurov wrote dozens of works that have since become classics of Kazakh literature. His literary repertoire spanned various genres, from dramatic portrayals of tribal life to satirical criticism of bureaucratic inefficiencies. Zhansugurov’s writings espouse timeless values and celebrate the indomitable spirit and love for the native land.

Early life and career

Born in 1894, he grew up in the Aksu district in the Almaty Region. He demonstrated a passion for music from childhood, mastering the dombra, a traditional Kazakh instrument, and participating in aitys, poetic contests.

Ilyas Zhansugurov with his family. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

After completing a two-year teacher’s course in Tashkent in 1921, Zhansugurov worked as a teacher in his village and contributed to the Tilshi newspaper as a reporter. He also engaged in writing school textbooks and translated works by renowned Russian authors such as Alexander Pushkin, Mikhail Lermontov, Nikolai Nekrasov, and Vladimir Mayakovsky into Kazakh, aiming to enhance access to literature.

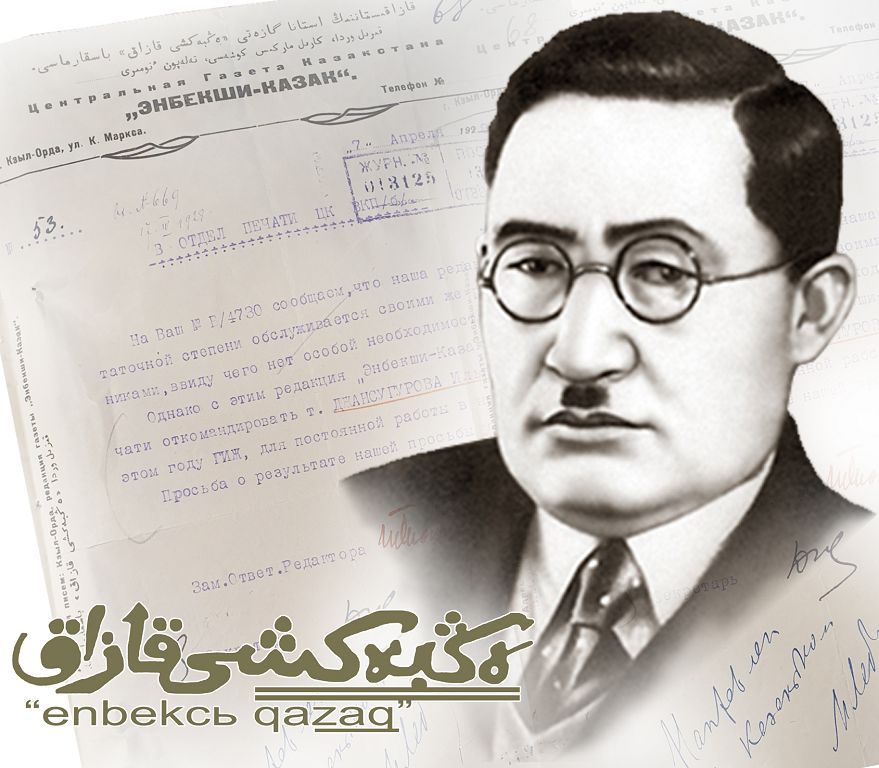

In 1925, Zhansugurov continued his education at the Moscow Institute of Journalism before joining the Enbekshi Kazakh newspaper (now Egemen Qazaqstan).

Recognizing his talent, the Kazakh intelligentsia elected him as the first chairman of the Writers’ Union of Kazakhstan in 1932.

Zhansugurov’s literary legacy

His earliest manuscripts date back to 1915 and 1920, reflecting his deep-rooted connection to Kazakh folklore and poetry. These early works, such as “Saryarka” and “Tilek,” were published in the Saryarka magazine in 1917.

Throughout his career, he expanded and deepened the thematic scope of his works, addressing contemporary and historical events while placing the people’s fate and interests at the forefront.

Second row, from right to left: Beimbet Mailin, Ilyas Zhansugurov, Saken Seifullin, Sabit Mukhanuly. In the third row, in the center, Abdilda Tazhibayuly. Photo credit: wikipedia.org

His notable works include 15 volumes of poems, such as “Kui,” “Dala,” “Kuish,” and “Kulager,” which are considered classics of Kazakh literature. These poems address societal challenges hindering progress, blending epic rhythms with lyrical depth to craft a distinct authorial style.

His novel “Oldastar” vividly portrays the life of Kazakh workers and their aspirations for freedom, depicting the events of the national liberation uprising of 1916.

In his classic pieces such as “Steppe,” Zhansugurov eloquently described the unique essence of nomadic life, depicting people’s resilient pursuit of happiness despite enduring years of hardship, trials, and adversity.

Kulager

“Kulager,” a standout work in Kazakh literature, emerged from Zhansugurov’s visit to the homeland of the renowned Kazakh composer and poet, Akan Seri, in Kokshetau, alongside Saken Seifullin, a pioneer of modern Kazakh literature.

During his visit, Zhansugurov met with local residents and learned about the tragic tale of the stallion Kulager, which inspired his work. The poem delves into a dramatic episode from Akan Seri’s life—the loss of his beloved horse—emerging as one of the most sorrowful pieces in national literature. In “Kulager,” Zhansugurov exposed societal vices and illuminated the subtle psychological intricacies of people living in the steppe. It served as an emotional outlet for him amid a period of political persecution. Completed in 1936, the poem was first published in the Enbekshi Kazakh newspaper.

The original manuscript of “Kulager” was lost when the poet was arrested, and copies of the newspaper where it was printed were confiscated from libraries. However, Kazakh writer Sapargali Begalin saved the newspaper copies containing the poem.

In 1937, Begalin discreetly stitched together the torn poem and concealed it within a pillowcase, preserving it for many years. Following Zhansugurov’s posthumous rehabilitation in 1957, Begalin entrusted the surviving newspaper clippings to Zhansugurov’s wife.

Lament for “Kulager” (extract)

The sun has set. The land of Arka is covered with the shadow.

The evening breeze ruffled Kusak Lake.

Akan grieved saying goodbye to Kulager,

while all the people looked on in sympathy.

Goodbye my Kulager, you must remain here,

I grieved because you fell because you will never rise

In this world, I live alone was beaten more than once –

It seems this is the fate that lies before me.

Kulager, I have made my public goodbyes to you

Your remains must stay in Zhylandy,

I have lost you my only one

Nothing I can do to bring you back to life.

…

Nothing can compare with your immense eyes,

How can I leave you here?

I should have hugged you for days like my own child,

Not leave you here to be sniffed out by dogs.

Kulager, goodbye my horse, my friend,

I know that you will never rise again

no matter how long I stay.

…

He left quickly with the orphan boy.

They went at a steady, slow pace till sunrise.

The way was long, the stars were bright.

The summer night grieved when it heard his song Kulager.

His inner sorrow transformed into a song,

singing with a bitter voice.

His song became like flowing water,

though not enough to extinguish the blazing fire.

Bitter grief and heavy sorrow resounded.

Every time he sang Kulager it brought forth all his sadness.

He kept the sleepy hollow ridge from rest.

He made the blind night sigh.

(Translated by Belinda Cooke)

Prosecution

Zhansugurov fell victim to political persecution in 1937. Falsely accused of plotting a national uprising, he endured imprisonment alongside literary fellows Beimbet Mailin and Saken Seifullin. Tragically, these three outstanding figures of Kazakh literature met a shared fate, as they were all executed in February 1938.