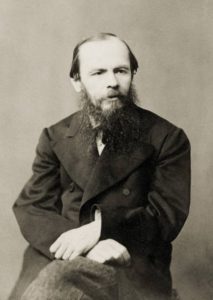

Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Photo credit: interesnyefakty.org

On the 11th of November this year, the world will celebrate an important anniversary that has a special meaning for both Russia and Kazakhstan: 200 years ago the world-famous writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky was born in Moscow, in a family of a Russian military doctor, Mikhail Dostoyevsky. The writer lived a tumultuous life of 60 years, which included an early literary success in the end of 1840s, a prison term in Siberia and exile in the Kazakh city of Semipalatinsk (now Semey), a return to a literary career in St. Petersburg and frequent trips to Europe… Now Dostoyevsky is one of the top ten most famous writers of the world and one of the most read ones, translated into 105 languages.

In Kazakhstan, Dostoyevsky’s memorial home museum in the city of Semey became one of the country’s 100 most important sacred sites, part of the list compiled by the First President of independent Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev. This forever made Dostoyevsky’s three years spent in Kazakhstan a part of the country’s “sacred geography.” This is only fair to both Dostoyevsky and Kazakhstan: Dostoyevsky is rightly considered a precursor of Eurasianism. In its moderate form, adopted in Kazakhstan, this ideological theory views Russia, Kazakhstan and other former territories of the medieval Golden Horde as a very special entity. These Eurasian countries form a part of the same cultural and spiritual space with “classical” Europe, but with a lot of unique characteristics and an ability to be open to both Europe and Asia.

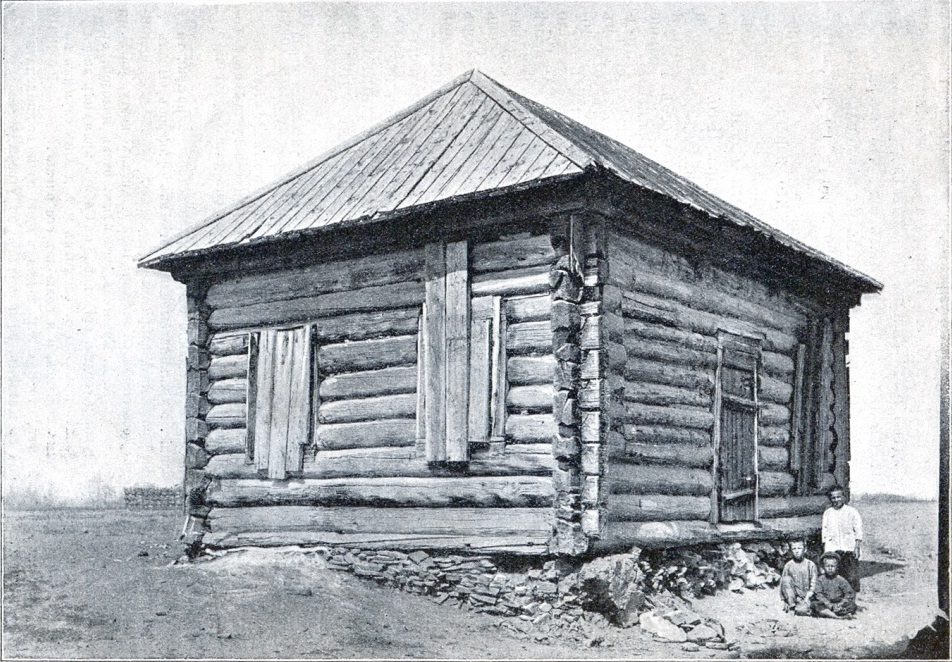

Memorial House-Museum of Dostoyevsky in Semey. Photo credit: avatars.mds.yandex.net

According to the World Almanac, Dostoyevsky has been a member of the world’s top ten most read writers since the first half of the twentieth century, mostly thanks to his deeply spiritual, dramatic and ultimately Christian novels of the 1860s and 1870s: “Crime and Punishment”, “The Karamazov Brothers,” “The Idiot” being the best known.

In Kazakhstan Dostoyevsky spent some of the most fruitful years of his life in the late 1850s, years which prepared him for the “writing marathon” of the 1860s and 1870s. The years of his stay in Semipalatinsk (which became Semey after the establishment of independent statehood of Kazakhstan in 1991) gave Dostoyevsky a lot of his first friends and his first experience of married life. (His wife Maria Isayeva became a prototype for several of his later famous female characters in Crime and Punishment and other novels.) But, most important, Dostoyevsky’s life in Kazakhstan molded his views and opinions, adding Eurasian depth to them and later allowing him to engage in dialogue with the West from the position of an equal, and not a humble imitator.

Illustrations of Petersburg artists Niki Velegzhaninova and Igor Knyazev to the literary works of Dostoyevsky at the exhibition in the Semey museum. Photo credit: kaz.rs.gov.ru

It was this Eurasianism, developed by Dostoyevsky in Kazakhstan, that found its expression in his famous narrative “The Gambler” written in 1866. In the text, the main character, a young Russian man addicted to gambling in Europe, reproaches the pragmatic attitudes of Germans in a peculiarly “Central Asian” way: “I would rather spend my life as a nomad in a Kyrghyz yurt, rather than waste it worshipping the German idol of amassing wealth!”

Philologists agree that this phrase reflects one of Dostoyevsky’s deepest impressions about Kazakhstan – the free spirit of its steppes. This image of a steppe as a space of freedom was most likely adopted by Dostoyevsky from his friendly exchanges with the great Kazakh enlightener and geographer Chokan Valikhanov – Dostoyevsky’s friend from his days in Omsk, Russian Siberia. When they got acquainted, Valikhanov, born in 1835, was a very young man, and Dostoyevsky had just finished his jail term in Siberia, a strict punishment that he received for participating in a Socialist group in the late 1840s.

Sculptural compositions of Chokan Valikhanov and Fyodor Dostoyevsky in Semey. Photo credit: tourister.ru

Historians found records of Dostoyevsky’s forays into the Kazakh auyls together with Valikhanov. (Later Valikhanov, who got an excellent European education in a cadet school, became the first Europeanized outsider since the medieval Marco Polo, who managed to visit the legendary Xinjiang area and its cultural center Kashgar, now on the territory of the Chinese People’s Republic.) It was thanks to Valikhanov that Dostoyevsky discerned the “Asian-Kyrghyz” side of Russia and learnt to look at it with respect and interest, rather than with chauvinism.

“Isn’t it a great challenge for you, isn’t it your sacred cause – to be the first to explain to Russia the role of the steppes in its history and the significance of your people for Russia?” Dostoyevsky wrote to Valikhanov in December 1856.

The house where Dostoyevsky lived during his exile in Semey. Photo credit: e-history.kz

No doubt that it was Kazakhstan that inspired Dostoyevsky to write the famous final lines of his novel “Crime and Punishment,” where the Europeanized Petersburg egotist Raskolnikov experiences a “rebirth” and returns to Christian kindness and humility during his stay in some nomadic land in the east of Russian Empire, where he is exiled for murder: “Raskolnikov looked at.. the endless steppe all lit by the sunshine, with only a few nomadic yurts lost in its space… There was freedom, and people previously now known to him led their simple lives. There the time stood still, as if centuries have not elapsed since the time of Biblical Abraham and his herds.”

The President of the Republic of Kazakhstan Kassym-Jomart Tokayev ordered a whole series of cultural events devoted to the 200th anniversary of the writer and expressed a hope that Dostoyevsky’s memorial museum in Semey will become a “magnet” for tourists from the whole world.