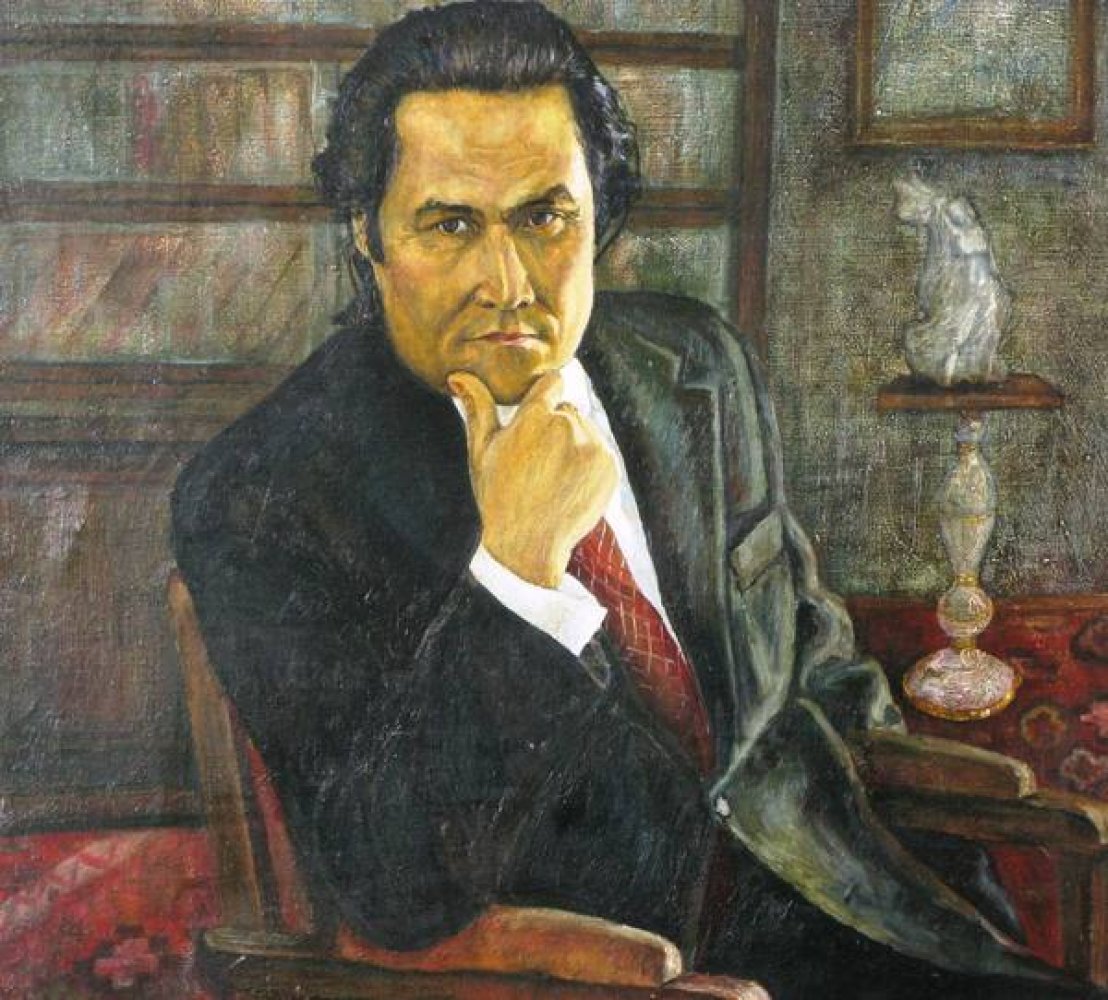

ASTANA — Kazakhstan marks the 95th anniversary of poet, writer and translator Mukagali Makatayev on Feb. 9, commemorating one of the most influential voices in Kazakh literature. His poetry, centered on homeland, grief and dignity, gained broader recognition only after his death.

Kazakhstan marks the 95th anniversary of poet, writer and translator Mukagali Makatayev on Feb. 9. Photo credit: e-history.kz

Makatayev wrote his first poem at 17. His first book appeared when he was 33. In the final year of his life, seriously ill and hospitalized, he composed nearly 4,000 lines in two months. He died in 1976 at the age of 45, and most of his works were published posthumously.

“The days without poems for me are lifeless. I thank God for giving me this consolation. A poet has his own world, his own society and his own universe. I live for this and fight for this,” Makatayev wrote in his diary.

Early life shaped by war

Mukagali Makatayev with his wife and kids. Photo credit: e-history.kz

Makatayev was born on Feb. 9, 1931, in the village of Karasaz in the Narynkol district of the Almaty Region, at the foot of Khan Tengri. The landscapes of his native land later became a recurring motif in his poetry.

He was born Muhametkali, but his mother later changed his name to Mukagali, believing that sharing the Prophet’s name placed a heavy burden on a child.

The eldest son of Suleimen and Nagiman, he grew up in a family that valued hard work and fairness. Although his childhood coincided with famine and repression, he later described his early years as the happiest period of his life.

That period ended when he was ten, and his father left for the front during World War II. Before departing, his father told him he was now responsible for his mother and younger siblings. He never returned. The family later received notice that he had died in combat. Years later, Makatayev reflected:

“I remember everything – my land and my life.

Only I do not remember whether I laughed or cried.

Only I do not remember –

Did I even have a childhood?” (author’s loose translation)

Like many children of the war generation, he worked alongside adults, herding livestock, plowing land and harvesting crops.

Writer and public figure Anuar Alimzhanov, a contemporary of Makatayev, later reflected on the responsibilities placed on children during the war years.

“By the age of 12, we could do everything: stand at factory machines if needed, drive caravans, protect village sheepfolds from wolves. We longed to sleep, longed to feel the cool touch of a clean cotton shirt. But there was no time for sleep, and instead of white fabric we wore sheepskin scraped by our grandmothers’ hands,” wrote Alimzhanov, describing how war and hunger forced children to distinguish edible roots and leaves, search for mountain onion and sorrel, and value even the simplest food.

“We learned patience, and we learned to rejoice in a kind word. We worked because we were needed – by our village, by our collective farm. Kindness was the most sacred sign of humanity,” he wrote.

Professional path and literary work

Makatayev began publishing in 1948. After finishing school, he worked as a village council secretary, headed a rural cultural center, served in Komsomol (short for the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) bodies and worked as a literary correspondent for a district newspaper. From 1954 to 1962, he was an announcer at Kazakh Radio and worked as a teacher.

Between 1962 and 1972, he headed departments at the Socialist Kazakhstan and Kazakh Adebiyeti (Literature) newspapers, and worked for literary journals. In 1972-1973, he served as a scholarly consultant at the Union of Writers of Kazakhstan.

His early collection, “Zhastar Zhyry” (Songs of Youth), was published in 1951. In 1962, the “Appassionata” poem brought him broader recognition. Over the following years, he published collections including “My Swallow,” “My Heart,” “Swans Do Not Sleep,” “Warmth of Life,” “Poem of Life,” “The Heartbeat,” and “River of Life,” which later entered the core body of Kazakh poetic literature.

Several of his poems were later set to music, among them “Sarzhaylau,” which became one of the most widely performed songs based on his verse. In the poem that gave the song its name, he wrote:

“…Vast steppe, woven like a green carpet,

Beloved homeland – there is no land equal to you.

Wide country, I return asking you to cradle me,

I come longing, missing you, thirsting for you.

Fresh spring water – sweet as honey, my remedy,

Cool breeze across your hillsides.

Oh my native land that sheltered me,

My Sarzhaylau, how I have missed you…” (author’s loose translation)

In addition to his original works, Makatayev translated major works of world literature into Kazakh, including Walt Whitman’s poetry, William Shakespeare’s sonnets and Dante’s “Divine Comedy.”

Personal tragedy and professional growth

During his life, Makatayev faced financial difficulties. Supporting a family of six children in the postwar period was challenging, and the family lived in rented housing for years. In 1964, his 11-year-old daughter Maigul was fatally struck by a motorcycle near their home in Almaty. The loss had a lasting impact on him.

In the following years, he lost a portfolio containing manuscripts, was dismissed from the Union of Writers in 1973, and faced sustained criticism in literary circles and in the press.

At a writers’ congress, he delivered a speech criticizing internal rivalries and favoritism within literary institutions. The speech, delivered in the presence of observers from Moscow, led to his removal from the hall and to further professional isolation.

“I cannot recall even a single day that left a joyful mark in my memory. I have entered my forty-fourth year, and my whole life appears so humiliating, so unbearable, that at times one wishes to leave it voluntarily. I once did not know what health was or what illness was. Now I have come to know every ailment,” Makatayev wrote in his diary dated May 31, 1975.

Years of stress took a toll on his health, and he was hospitalized later that year. During that period, he devoted himself intensively to writing.

“After many shocks, both moral and material, I found myself in the hospital. The hospital helped me. After a long separation, poetry and I met again. In two months, I wrote nearly four thousand lines. I worked honestly, without thinking whether anyone would publish them,” he wrote.

Those works were not published during his lifetime.

Final years and posthumous recognition

Mukagali Makatayev died on March 27, 1976.

His son Zhuldyz later recalled that his father once asked him, “If I die and they ask you what kind of man he was, what will you answer?” Zhuldyz said he could not respond clearly at the time. According to him, Makatayev then said, “Tell them that I was a man with a child’s soul. Then you will be completely right.”

In 2000, Makatayev was posthumously awarded the State Prize of Kazakhstan for his “Amanat” poetry collection. In 2002, a bronze monument was installed in Almaty. His works continue to be republished, studied and performed, and his translations remain part of Kazakhstan’s literary heritage.

Ninety-five years after his birth, Makatayev’s poetry remains widely read, reflecting themes of homeland, personal dignity and moral responsibility that continue to resonate across generations.