ASTANA — Experts and officials gathered for an online conference on Jan. 29 to discuss how water availability and potential deficits could affect Kazakhstan’s food security, particularly across irrigated crops and livestock. With inflation at 12.3% in 2025, experts said water efficiency will be necessary to stabilize the domestic food supply and contain price pressures.

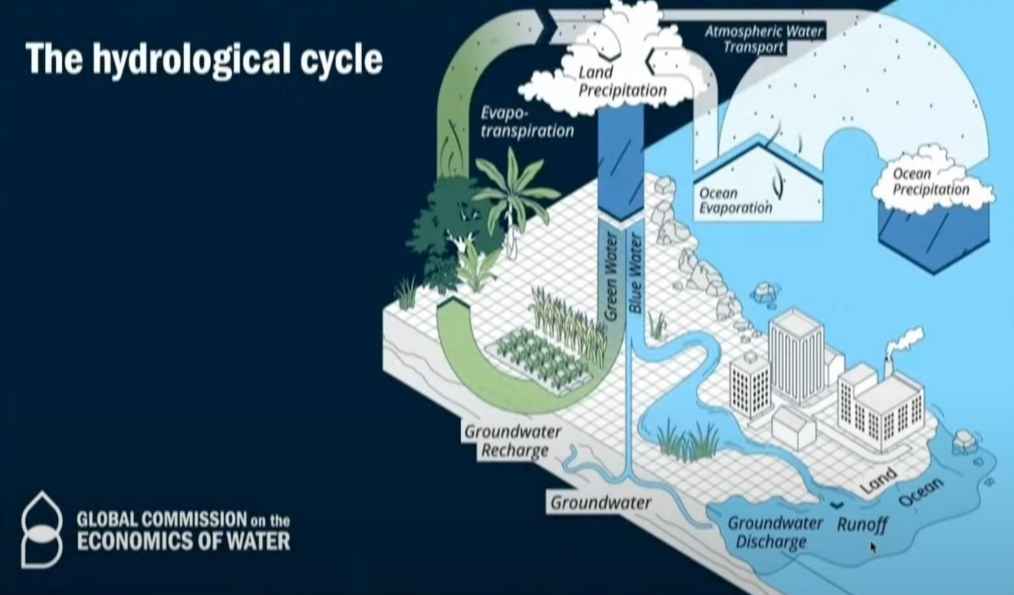

The hydrological cycle. Disrupted water cycles drive global risk, says Yessekin. Photo credit: Yessekin’s presentation / Global Commission on the Economics of Water report

Water scarcity is no longer a narrow agricultural issue. It is also an economic, social, and geopolitical challenge, with experts noting that competition over shared rivers, rising consumption, and weak governance could amplify risks to farming regions and urban centers.

What drives water deficit in Kazakhstan

Rahimbek Abdrakhmanov, the head of the center for political-economic analysis. Photo credit: Forbes.kz

Rahimbek Abdrakhmanov, the head of the Center for Political-Economic Analysis, said water deficit should now be treated as a first-order risk with broad economic and social consequences.

Citing the Eurasian Development Bank data, he said water losses in transport and agriculture reach 40-50%, meaning significant volumes are lost before reaching fields or economic use. He also referred to regional research indicating that tensions linked to transboundary rivers have increased over the past decade.

“From 2014 to 2024, the number of conflicts in Central Asia linked specifically to water use, transboundary rivers and related issues increased significantly. (…) The risk of water deficit is one of the most important risks for Central Asian countries, and it can trigger cascading problems, including food security, migration and others. A third of Central Asia’s population does not have access to clean drinking water,” said Abdrakhmanov.

Climate, shared rivers and uneven geography

Marat Imanaliyev, the deputy director of the water policy department at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation. Photo credit: 24KZ

Marat Imanaliyev, the deputy director of the water policy department at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation, said Kazakhstan is experiencing declining river inflows alongside uneven water distribution. Eastern and southeastern regions rely more heavily on local surface water, while the south, west and central areas face sharper deficits relative to population and economic activity.

Seasonality has also become more pronounced, he said.

“When water is needed, during the vegetation period, it is not there, but it is there when it is not needed,” said Imanaliyev, linking this shift to changing precipitation patterns and climate trends.

On transboundary coordination, he said Kazakhstan has water-sharing agreements with Russia, the Kyrgyz Republic and Uzbekistan, and continues negotiations with China over shared rivers, including the Ili River, which flows into Lake Balkhash.

Agriculture and livestock at risk

Bulat Yessekin, an international expert and coordinator of the Central Asian platform on water management and climate change. Photo credit: Central Asia Climate Portal

Experts emphasized that agriculture remains the dominant water user. Imanaliyev said approximately 90% of water withdrawals go to irrigation, much of it effectively nonreturnable.

Bulat Yessekin, an international expert and coordinator of the Central Asian platform on water management and climate change, said the speed of water decline is becoming a direct threat to food supply planning. He pointed to irrigated farming in the south as an example of scale.

“In this year alone, irrigation in the southern regions took 11 billion cubic meters of water,” he said, noting that as shortages deepen, agriculture will take the first hit, and the consequences will spread through food prices, rural livelihoods and trade decisions.

Arsen Islamov, a livestock farming expert. Photo credit: El Dala

Arsen Islamov, a livestock farming expert, said the debate over crop substitution should include how farmers adapt on the ground. He raised the idea of shifting from rice to crops such as alfalfa, which can support animal feed and reduce soil erosion, while also questioning how much river flow ultimately depends on glaciers versus seasonal rainfall.

At the same time, he highlighted that rice should be viewed within the broader structure of regional food supply. Kazakhstan’s northern grain belt, including the Kostanai, Akmola and North Kazakhstan regions, underpins staple food security across Central Asia.

“We are a wheat civilization, not a rice civilization,” said Islamov, highlighting that flour-based staples dominate diets across much of the region.

“Green water” and the broken water cycle

According to Yessekin, the water crisis is not only about shortages in rivers and reservoirs, but also about a deeper disruption in the water cycle, especially what specialists call “green water,” the moisture stored and moving through soils, vegetation and the air.

Referring to discussions at the 2024 One Water Summit, held under the initiative of France and Kazakhstan, he said participants warned that global water flows are being destabilized, even as the planet’s total water volume remains broadly unchanged.

“At that summit, it was reported that for the first time in human history we have disrupted the planet’s global water flows. (…) The total amount of water on Earth stays roughly the same, only a very small share escapes into space, but we have disrupted how water moves,” said Yessekin.

He said conventional models of the water cycle – evaporation, precipitation, glaciers and rivers – overlook the critical role of green water, which he estimated accounts for approximately 65% of total flows.

“The key cause of the crisis is the disruption of hydrological cycles, the disruption of green water flows. (…) We assumed nature would keep replenishing it. Nature has stopped doing that. That is why current management models are no longer sufficient,” he said.

“In our strategies, water is treated primarily as an economic resource, rather than as a factor that sustains water availability, biodiversity and climate stability. (…) There are more than 18 international institutions working on different aspects of water, but there is no comprehensive system focused on maintaining the water cycle itself,” Yessekin said.

He said basin-level management is central to water security because it brings together different sectors, removes institutional barriers and helps coordinate decisions not only across industries but also across national borders.

“When we were drafting the Water Code, more than 500 proposals were adopted. But the main proposal – strengthening basin councils through the transfer of real authority, as is done in France, Canada and other countries – still needs to be implemented. This must be done urgently. It is the main solution to the interconnected problems of food security, water, climate and biodiversity,” said Yessekin.

Efficiency measures and what works now

Kuralai Yakhyayeva, an expert at the Kazakh branch of the Scientific Information Center on Water Management, presented examples of water-saving measures tested in the lower Syr-Darya in the Kyzylorda Region, a major rice-growing area.

A pilot project launched in 2013 introduced water-measurement tools, stricter accounting, and laser land leveling to improve distribution. In the pilot area, water use declined while yields were maintained.

“In 2013, more than 31,000 cubic meters of water per hectare were applied. On the pilot site, it was 22.5. Water savings were 28%, and yields did not decrease,” said Yakhyayeva.

She also described hydromodule calculations used to reassess crop water allocations and reduce waste across agriculture, municipalities and industry.

Rice producers urge gradual transition

Sagidulla Syzdykov, an expert at Kazakhstan’s rice producers and processors association and a commercial director of GP Abzal&Company. Photo credit: El Dala

Sagidulla Syzdykov, an expert at Kazakhstan’s Rice Producers and Processors Association and a commercial director of GP Abzal&Company, agreed that rice is water-intensive but said commonly cited consumption figures are outdated due to improved irrigation practices.

He stressed that Kyzylorda’s climate and production economics limit how quickly farmers can shift to other crops.

Rice cultivation remains a key rural livelihood. At the same time, he said the water deficit has been felt in the region for the past eight years and linked it to both climate change and the upstream expansion of irrigated land in neighboring countries.

Water governance as food security policy

Imanaliyev said the ministry is developing basin-level plans and long-term forecasting tools to guide allocation decisions. He acknowledged that abrupt restrictions on farmers without viable alternatives could create social strain and said allocation decisions in low-water years are increasingly routed through basin councils.

Yessekin added that water-saving measures alone will not be sufficient without restoring natural cycles.

“If we only do water saving, it means we are spending our bank account more carefully without replenishing it. We need to stop wasting water and start restoring water flows through restoring land, forests, vegetation and catchment areas,” he said.