November marks the 190th anniversary of Shokan Ualikhanov’s birth. The exact day is lost to history, but we know he was born in 1835, in Amankaragai village in the Kostanai Region, into Kazakh nobility. His father Shyngys was a grandson of Ablai Khan. Later, his family moved to the Kusmuryn fort, but young Ualikhanov spent much of his childhood under the care of his grandmother, Aiganym, at her manor in Syrymbet.

Childhood and early curiosity

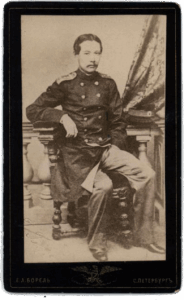

Ualikhanov upon entering the Siberian Cadet Corps: Wikimedia/Xhancock

Aiganym was the second wife of Uali Khan, son of Ablai Khan, and a woman of extraordinary influence. She played a major role in enhancing Kazakh-Russian relations, to the point that the Russian Emperor Alexander I ordered the construction of a manor for her in Syrymbet (today in the North Kazakhstan Region). This was a cultural and educational hub: a main house, guest rooms, a school, a mosque, a madrasa, a bathhouse, and various outbuildings. Ualikhanov grew up surrounded by books, intellectual discussion, and encouragement to observe and understand the world around him.

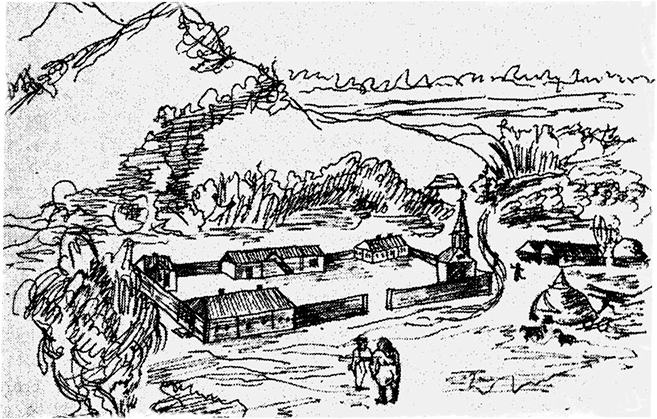

The manor itself endured a turbulent history. It was partially burned during Kenesary Khan’s uprising and dismantled under the Bolsheviks, its logs reused for local cottages and a House of Culture. Archaeologists only began uncovering its foundations in the late 1980s. Ualikhanov’s own pencil drawing, depicting the three-winged residential house, the mosque, and outbuildings, was invaluable in reconstructing the estate, which was restored in 1991 for the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Shokan’s own pencil drawing of the manor in Syrymbet. Photo credit: shoqan.kz

From an early age, he showed extraordinary versatility. He loved to draw, inspired by the topographers and artists visiting Kusmuryn, and sketched the surroundings of Syrymbet, capturing everyday life with remarkable attention to detail. His father encouraged this curiosity, taking him on archaeological excursions where young Ualikhanov not only drew the artifacts they discovered but also sought to understand the people who had made them: their lives, customs, and beliefs. This combination of artistic sensitivity and scholarly curiosity became a defining trait: a mind that could appreciate beauty while rigorously seeking knowledge.

Education and intellectual growth

At the age of 12, Ualikhanov entered the Omsk Cadet Corps, where his intellect, memory, and diligence set him apart. He quickly gained the admiration of his teachers, particularly in history, geography, and Oriental studies. It was here that he formed a lifelong friendship with the distinguished Russian scholar Grigory Potanin.

Ualikhanov’s portrait taken during his time in St. Petersburg. Photo credit: shoqan.kz

“Ualikhanov is too European, more European than many Russians. And even when he returned to his native steppe, lying on Bukhara carpets and colorful pillows, dressed in a beshmet (long tunic) and Kazakh dombal (traditional round headwear), he still remained a European. He read French literature and never renounced European manners. He could never shed the imprint of European spiritual culture and become a nomad,” Potanin wrote later, reflecting on his friend.

I disagree. To me, this is precisely the essence of a nomad: the ability to remain deeply rooted in your culture while observing it from the outside, preserving its authenticity for future generations, while staying open to the beauty and progress of the wider world.

Graduating at 18, he was commissioned as a cornet in the cavalry, but the uniform did not confine him. He was always exploring — geographically, intellectually, and culturally. He participated in expeditions across Central Kazakhstan, Zhetysu, and the Tarbagatai region, mapping territories, collecting specimens, recording folklore, and studying local laws and customs. His curiosity spanned from the scientific to the humanistic: ornithology, botany, geography, history, ethnography, and the law of his people.

During his time in Omsk, Ualikhanov also met Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was then in exile at the Omsk fortress. The two exchanged letters later in life. In the last of the four known letters from Ualikhanov to Dostoevsky, Ualikhanov provides a detailed account of his participation in the elections for Senior Sultan of the Atbasar District. During the process, he experienced opposition both from some of his own people and from Russian officials, who did not want an educated man with democratic views to become Sultan.

In the letter from Kokshetau, dated Oct. 15, 1862, he wrote: “At one point, I considered becoming a sultan, not for prestige, but to devote myself to the service of my people—to protect them from the arbitrariness of officials and the tyranny of wealthy Kyrgyz. More than anything, I wanted to show by my own example how an educated sultan-ruler could truly serve his people. They would see that a genuinely educated man is not like a Russian official, whose actions had shaped their opinion of Russian education. With this aim, I agreed to stand for election as a senior sultan of the Atbasar district. But the process was far from straightforward: the officials—both regional and administrative—rose unanimously against me. You can imagine why…”

Exploration and scholarship

Ualikhanov’s scholarly output was staggering. He recorded the Kyrgyz epic “Manas,” partially translating it into Russian and conducting historical and literary analysis, examining the hero, the story’s structure, and its cultural significance, a gift that helped preserve this oral tradition. In 1858–1859, he undertook his famous expedition to Kashgar, establishing his reputation as a fearless traveler and meticulous scholar. He studied geography, history, politics, and daily life, producing “On the State of Altishahr,” or the Six Eastern Cities of the Chinese Province of Nanlu (Little Bukhara) — the first comprehensive scholarly study of Eastern Turkistan.

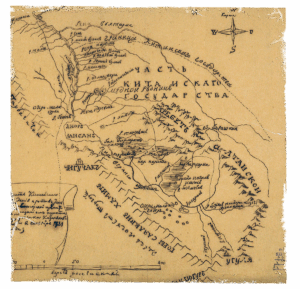

Map of the borderlands with China, from Ualikhanov’s archive, 1857 Photo credit: shoqan.kz

Back in St. Petersburg, he worked at the Military Scientific Committee and the Asian Department, prepared maps, compiled ethnographic research, and lectured at the Russian Geographical Society. In 1857, he became a full member of the Society. He also had a refined aesthetic sense. As writer and journalist Zharylkap Beisenbayuly, who dedicated much of his life to researching Ualikhanov’s biography noted:

“Shokan always dressed impeccably; in winter, he wore a military coat with a beaver collar, cared for his nails, and let one grow long ‘in the Chinese style.’ He loved beautiful objects, collecting cigarette cases for their artistry and ideas, not their value. On one was a rat drilling into the earth, which to Shokan represented a geologist,” Beisenbayuly wrote.

Ualikhanov traced historical water systems, studied wind currents from the Dzungarian Gate, and delved into chronicles to illuminate centuries of Central Asian life. Yet despite his brilliance, life was fragile. The Kashgar expedition strained his health, and in 1861, he returned to the steppe, hoping to recover. But illness prevailed, and in April 1865, Shokan Ualikhanov passed away in Koschentogan, at the foot of the Altyn-Emel Mountains. He was only 30 years old.

Lasting legacy

In 1904, the Russian Geographical Society published his collected works. Russian academician Veselovsky wrote: “Like a brilliant meteor… Shokan Ualikhanov flashed across the field of Oriental studies. Russian orientalists recognized him as a phenomenal figure and expected from him great revelations about the fate of the Turkic peoples, but his untimely death deprived us of these hopes.”

Russian scholars called him a brilliant meteor, as Kazakh writer Sabit Mukanov echoed in his trilogy about Ualikhanov, a figure who blazed across the field of Oriental studies, brilliant but fleeting. Yet a meteor burns brightly and disappears; Ualikhanov was different.

To me, he is inseparable from the landscapes of my childhood: the hills of Kokshetau, the forests and lakes of Burabay. He embodies curiosity, courage, and the restless spirit of a true explorer. His letters, sketches, maps, and writings continue to inspire, showing that to truly know the world, one must engage it with both intellect and heart. For young people in Kazakhstan today, as for me, Shokan Ualikhanov is not a fleeting meteor. He is a guiding star, a constant light illuminating the path of discovery, understanding one’s culture, and embracing the wider world, leaving an enduring legacy for generations to come.