Every nation has its own literary titans, often hailed as “great” or “the founding father” of certain traditions in the literary domain. Poet Abai is a monumental figure for Kazakhs in this sense. From the moment you enter the first grade, the notion of his greatness is inscribed in you as something unquestionable, indisputable. To challenge that is not a matter of opinion but as a sign that you haven’t yet matured enough to fully appreciate the depth of his legacy.

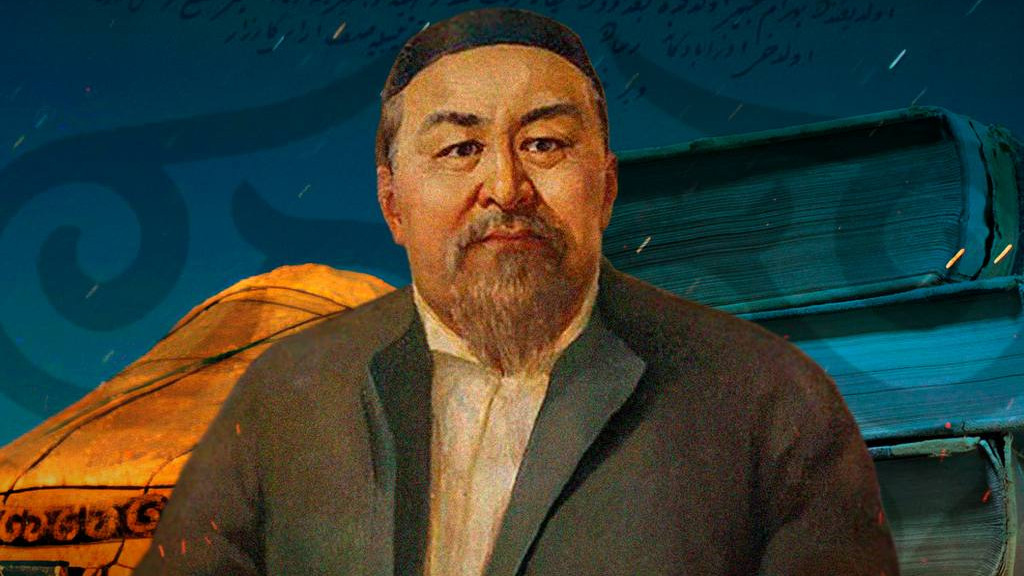

Abai is hardly neglected in Kazakh life. His monument is inside us, passed down through the generations. Photo from kazaknews.kz

This year, Aug. 10, is the 180th anniversary of his birth, and since big anniversaries only come around once every 10 years, I thought I should figure out what Abai’s legacy means to me. So, rather than taking his greatness for granted, I decided to trace the influence of Abai’s poems and words of wisdom through my childhood and adulting.

My first encounter with Abai

The first time I encountered Abai was in the first grade. We had to learn by heart one of his short poems:

“Don’t be too captivated by everything

If you are an artist, be brave.

You, too, are a brick in the world,

Find your niche, go, stay!” (author’s loose translation).

Honestly, the only word I understood at that time was “brick.” So it became a poem about bricks.

Aibarshyn Akhmetkali. Photo from personal archive.

It was only after graduating from university and coming across the last two verses as someone’s yearbook quote that I could grasp the profoundness of the message. Stepping into adulthood, I spent the next years trying to force myself to “fit” into places I didn’t fit. And only after a few failures did I finally find my place in writing, which led me to become the journalist I am today.

As with most good poetry, the impacts — in this case, of knowing who you are, of someone’s value to society, of compatibility and courage — are only understood through life experience.

Learning to trust myself

Fast forward seven years, and there I was, a teenage girl going to middle school. Kazakh literature was my favorite subject. The literature teacher felt especially close to me, not just because she taught the material well, but because she genuinely wanted us to grow up into decent human beings.

One day, she had the entire class memorize the following verses by Abai, saying that as we stepped out into the world, the lines should serve as our compass:

“Do not believe the flatterers, for they

Are certain to betray you one fine day.

Trust only in yourself. A sober mind and toil

Will happiness and weal for you purvey.” (Translated by Olga Shartse).

“Trust only in yourself,” taught me not only to believe in my own abilities, but to trust my inner feelings of what is right or wrong for me. So when the time came to change my career path, I chose to listen to myself, even when the words of others sounded tempting.

Over the years of my ups and downs, I’ve returned, again and again, to the memory of my teacher and the wisdom she put in me through Abai’s poem.

What it takes to become a writer?

Perhaps the closest I’ve felt to Abai’s words was when I decided that I want to write something of my own. Working as a journalist means I often tell other people’s stories, but once I decided to share my own thoughts on social media, I was suddenly filled with doubt.

Abai started writing his philosophical “Kara Soz” (Book of Words), consisting of 45 brief parables, when he was 45. Feeling that he had pursued every material and spiritual goal, he decided to make “pen and paper my only solace.”

“Should anyone find something useful here, let him write it down or read it. And if no one has any need of my words, I say ‘my words are mine.’ And now I have no other concern than that,” said Abai in the very first word.

As a writer, the fear that your words don’t matter or aren’t needed by anyone is one of the deepest. That’s why Abai’s words, that if you don’t need his thoughts, then they will simply be for himself, resonated so deeply with me. They gave me enormous freedom. Now, when I hesitate to share something of my own, I tell myself: even if no one needs these words, they still belong to me—and that’s enough.

Is Abai relevant to the world?

Abai is hardly neglected in Kazakh life. His monument is inside us, passed down through the generations. It is in the phrases we use, the poems we cite, the wisdom we pass, and the lines that make us suddenly realize we’re not that different.

We often wish for our greatest poets and writers to be known around the world—as if global recognition somehow validates our nation or proves we are worthy of producing “greatness.” But I’ve come to believe that not every voice is meant to be broadcast globally.

Abai wrote for the Kazakh people, for his own people. Not from a place of superiority, but out of regret that so many were wasting their lives on things that do not matter or are superficial, like envy, anger, and the empty pursuit of power and wealth. His messages are universal, but the way he expressed them was deeply rooted in the Kazakh spirit, in a language that speaks directly to us.

I think it is we, Kazakhs, who should first and foremost honor his legacy. If the world comes to know him too, that’s good—but for me, it’s not the goal. It was a joy to mark the gift that Abai has given me, and therefore to many more people in this country, for the past 180 years.

Have you ever noticed how, when we meet someone from another country, we often mention a famous name from their homeland? What names come to your mind when you meet someone from Kazakhstan?

If, alongside Genady Golovkin, Shavkat Rakhmonov, or Dimash Kudaibergen, you leave this page remembering one more name—Abai, a voice of the Kazakh people—then my job here is done. Thank you!