With the fifth World Nomad Games almost upon us, it is perhaps a good time to look into the remarkable history of these sports. We know that nomads throughout the whole of Central Asia have participated in competitive sports for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. As with the Olympic Games, the nomadic games were rooted in physical strength and preparation for combat. For the Greeks, of course, it was javelin, discus, wrestling and sprinting, whereas for the nomads it is horse racing, wrestling and archery that form the core sports. Even the board game Togyzkumalak (and its West African equivalent, Oware) – in which competitors attempt to collect a certain number of beads – can be seen as training in strategy for military commanders.

The board for the strategy game Togyzkumalak.

There are precious few written records, particularly early ones, that give an indication of how sports on the steppe were conducted. In Mongolia, the three great ‘games of men’ – archery, horse racing and wrestling – are mentioned in the Secret History of the Mongols, where they are still celebrated at the annual Naadam festival. This great festival has been held annually since 1639 and is celebrated in every part of the country.

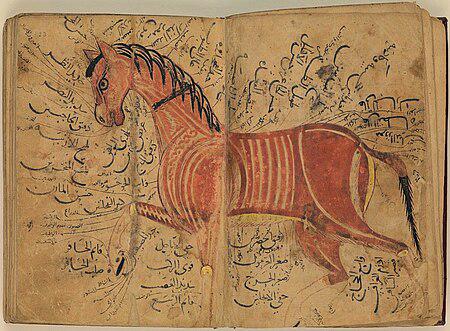

Already, by the late 1300s CE textbooks setting out rules and techniques for archery were in circulation. The Mamluk rulers in Egypt and Syria, most of whom were descendants of nomadic Qipchaq Turks from the Kazakh steppes who had once been part of the Golden Horde, developed the Furusiyya – military manuals which taught cavalry trainees how to prepare their clothing for archery practice, how to make the ‘Falcon’s Talons’ to grip the bow correctly and how to develop their strength. A novice started with a featherless arrow which he shot time and again at a target only a bow’s length away. Tayburgha al Kaklamish al-Yunani, a Mamluk of Qipchaq origin, wrote a 200-line poem giving complete instructions on archery, which the novices were expected to learn off by heart.

Page from a Mamluk manual on horses (pic from approx. 1300)

As a top priority the Mamluk troopers were also taught to use the bow from the saddle and to put on and completely remove armour while riding a horse. They were taught about how to look after a sick horse and to keep their horse tack in good condition. We have accounts from the 15th century CE of Mamluks taking part in competitions called qabaq in which they had to shoot an arrow down at a sand-filled basket and up through a ring mounted seven metres off the ground. Only after perfecting both shots could a trooper attain the status of a trained warrior. When emissaries from the Golden Horde, predecessors of the Kazakh Khanate, paid a visit to the Mamluks they would watch archery competitions that lasted several days.

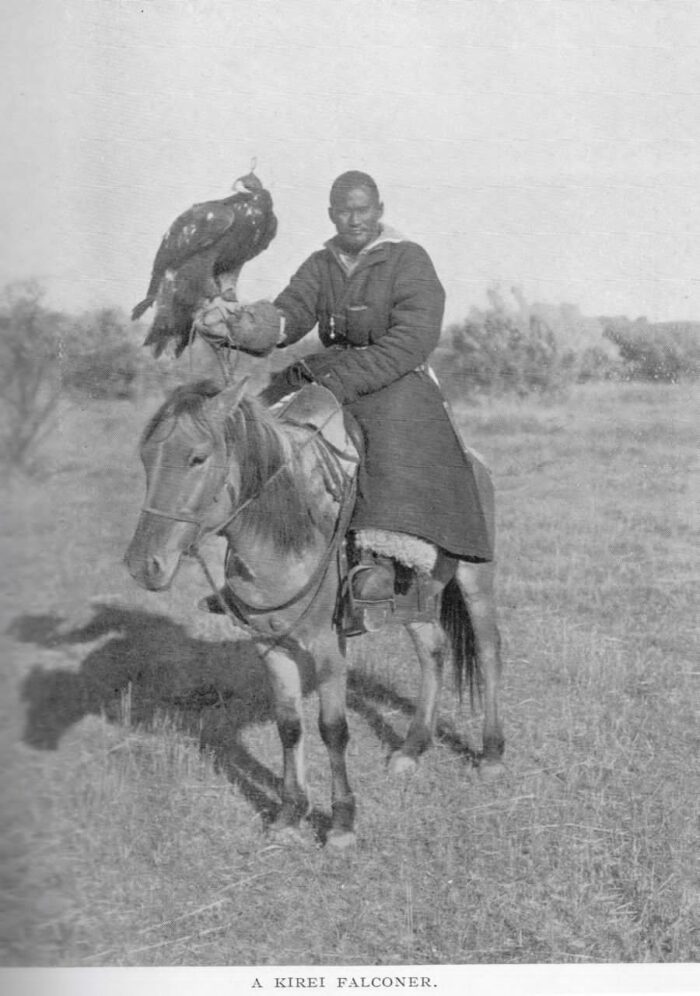

Eagle hunting has always been popular on the steppe (pic from approx. 1890)

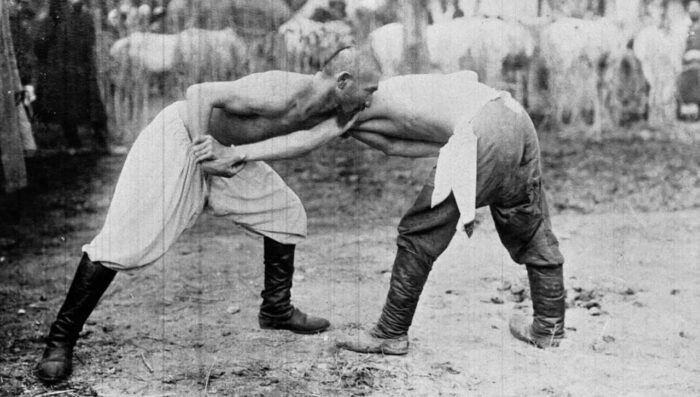

Just a few years later, in 1403, ambassadors from the Spanish King Henry III of Castile, led by Ruy Gonzalex de Clavijo, travelled to Samarqand to the magnificent tent city of Timur (Tamerlane). Clavijo’s detailed account of what he saw at the great tent city outside Samarqand includes a description of a wrestling competition: “These wrestlers were dressed each in a leathern garment like a sleeveless jerkin and at first struggling together it seemed as though neither could overcome the other. It was commanded them, however, to have done, and then one quickly threw his opponent, holding him down for a long space of time and preventing his getting up, for had he been able to get up again it would have been held that his fall was not a defeat.”

By the 18 century these great sporting events were coming to the attention of European travellers. In 1736, for example, the English traveller John Castle, who at the time was attached to the Russian Orenburg Expedition, set off into the Western Kazakh steppe to visit Khan Abul Khayir, sultan of the Junior zhuz, whose camp lay several days to the south. It was here that for the first time Castle came across the large eagles – bercut – used by the Kazakhs for hunting: “A stand was set up on the front part of the saddle, on which it sat and when the occasion arose, given that we encountered many wild goats and horses, it would be released at different times and achieve this effect, whereby as soon as it reached just on the world prey, it would attack its eyes with its talons and blind it, and thereby furnish the occasion for killing it easily.” Castle was also present when Abul Khayir hosted a horse-racing competition, providing a robe of honour as a prize to the 12-year-old winner.

Gradually, as cavalry and archery declined in favour of modern methods of warfare, the need for military training and competition declined. In its place, from the middle of the 19th century, we see the beginning of huge gatherings to commemorate the death of a prominent khan or sultan.

The great Kazakh historian and scholar Chokan Valikhanov recorded this tradition in 1856 when a Kyrgyz bard recited for him the epic poem The Memorial Feast for Kökötöy Khan, which describes in detail the Funeral Games and Horse Racing, together with ‘Heroic Brawling’ that accompanied the funeral of the eponymous hero. As one commentator notes, it shares its themes of sport and remembrance with the 23rd book of Homer’s Iliad.

Kazakh kuresi wrestling (pic from approx. 1890)

A few years later we also get an account of horseracing from American diplomat Eugene Schuyler, whose 2-volume Turkestan is a brilliant description of steppe culture in the 1870s: “A circumcision, a marriage or a funeral feast among the Kazakhs is the signal for a large festival, accompanied by games and horse races. To these, men will sometimes ride one or two hundred miles for the mere chance of regaling themselves for two or three days at another’s expense and take their share of gorging on whole-roasted sheep and horses.” Schuyler says races are sometimes up to 20 miles long and large prizes are offered: “I was invited to a toi, or feast, near Aulie Ata (now Taraz), where it was said would be some celebrated racers from Khokand and the highest prize was as much as 500 roubles, which to a Kazakh is a very great sum,” he writes. Schuyler also describes wrestling and kokpar, “where one man holds a kid thrown over his saddle and everyone else tries to tear it from him.”

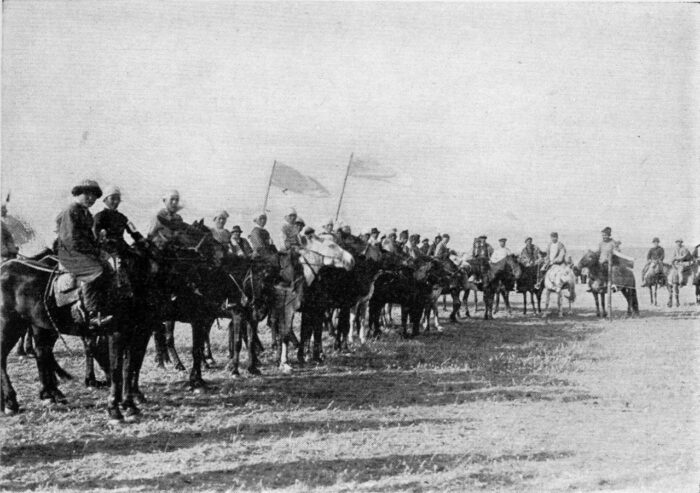

Not long after this we get our first photographs of nomadic games. The Turkestan Album, a six-volume photographic and artistic record of Central Asia in the early 1870s drawn up on the orders of the first Governor-General of Turkestan, General Konstantin Petrovich Von Kaufmann, includes several pictures of horse races. William Bateson, a British scientist who spent 18 months in northern Kazakhstan in the 1880s tells how he paid for a sheep carcass for a kokpar competition.

A photograph from the Turkestan Album, showing riders preparing for a race (pic from approx. 1870)

Nelson Fell, a copper-mining engineer lived on the steppes close to Karaganda for seven years between 1902-1908. He records how in November 1907 he was informed about the death of Sultan Hacen Akaev at his winter quarters near by. “As in Ireland, a funeral is made the occasion of elaborate ceremonies and feastings, so in Kazakh land, the custom is that a notable man, before he dies, makes all necessary dispositions for a great festival, to be held six months or a year after his death, to which all his friends and the whole countryside shall be invited. In this way, not only does the dying man provide in a worthy manner for the dignity and honour of his family, but he also carries with him beyond the grave, the tradition and law of Kazakh hospitality”.

Fell calls such a festival a pominka, a Russian word, but it is more usually known in Kazakh as Eske salu as. Six months after hearing the news of Sultan Akaev’s death, he set out on horseback in his finest clothing and with the horses decked out with silver-mounted bridles. The event lasted for three days, with wrestling being particularly popular. Fell records that even women engaged in hard-fought bouts, for which he provides a photograph for proof, presumably thinking that no-one would believe him without one.

Nelson Fell’s photo of women wrestling (pic from 1907)

He adds that the kokpar drew the largest crowds: “It is a rough sport and so is the wrestling on horseback, but everyone is so good-natured and good-humoured, that it is rare that anyone is hurt.” Fell also mentions eating competitions, in which two auls are pitted against each other and during which enormous amounts of food are consumed. Typical for one man would be

an entire sheep, eight gallons of kumiss and two gallons of tea. The festival ended with the horse racing, where young boys gallop for anything up to 20 miles in the hope of winning a prize, that is just as quickly distributed amongst his friends.

Fell’s photo of a horse race – baiga (pic from 1907)

Thus we can see that the nomadic games, based around the three great disciplines of horse-racing, archery and wrestling, have been a component part of Eurasian nomadic culture for millenia. Once they were specifically for military training, but later they marked important celebrations and remembrances. During the Soviet era most of these sports were less widely celebrated, but they never stopped entirely. Since Kazakhstan’s independence, they have been the subject of a remarkable revival, a celebration of national identity. The first Nomad Games took place in 2014 in Kyrgyzstan with just ten sports and competitors from 19 countries. Today the World Nomad Games in Astana from 8-13 September will include more than 3,000 competitors from more than 100 countries. The Games themselves are included in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List and with thousands of competitors taking part from all over the world, their future is assured.

The author is a British author and journalist.