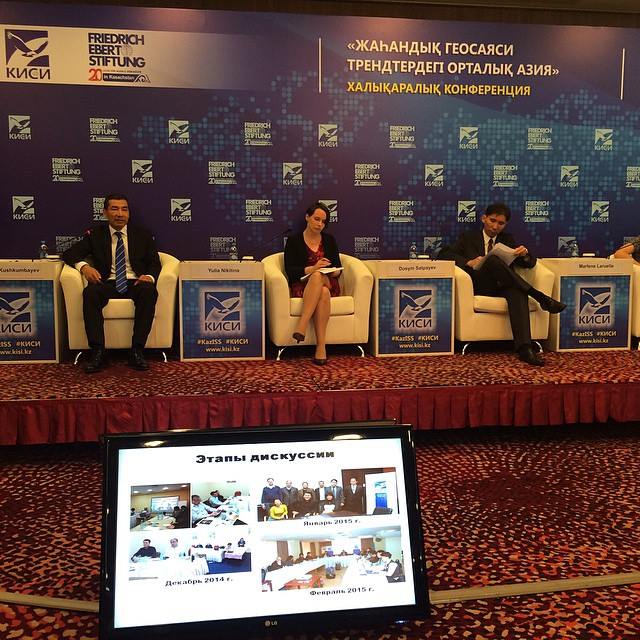

ASTANA – On June 18, experts from three continents discussed some of the thornier geopolitical issues in Central Asia today, including foreign policy failures, the political and economic impact of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the lack of trust between states of the region and the urgent need for reform. The discussions took place at the Central Asia in Global Geopolitical Trends conference organised by the Kazakhstan Institute of Strategic Studies (KazISS) and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation Office in Central Asia.

“We [in Central Asia] sharply, physically feel how our region is being pulled into geopolitical processes,” said Secretary of the Security Council and assistant to the President of Kazakhstan Nurlan Yermekbayev in his opening remarks. “I don’t want to exaggerate the challenges, but yes, there are in Central Asia and in many other parts of the world today unprecedented, accelerated information and other processes which force us not only to respond quickly but also to foresee possible scenarios.”

The forum gathered experts for panel discussions and question sessions on “The Transformation of the International Relations System,” “Central Asia 2020 Development Models” and “Potential and Prospects for Central Asian Integration.” It witnessed both optimistic and pessimistic views as well as voices not often heard.

One of these voices was Amrullah Saleh, head of the Green Trend political party of Afghanistan, who reminded participants that his country is “not going away” and that eventually, the region will have to increase its engagement with their neighbour. “If you think containment of Afghanistan is cheaper, you are making a mistake,” he said. “Engagement is much cheaper than containment, and disengagement is an illusion.” Look at Afghanistan as a new country, he suggested to participants – one that is energy thirsty and provides access to energy-thirsty Pakistan and India; one that is eager to develop transit potential, including the Northern Distribution Network; and one with a thriving civil society.

Regarding Central Asian integration, participants again hit upon the issue of trust between the neighbouring states. We know we have shared problems, said Dosym Satpayev, director of the Almaty-based Risk Assessment Group, but we don’t solve them together. Difficult issues like water use and regional security are not going to disappear, and can only be addressed jointly, several participants echoed. There were calls for more frequent and honest discussion fora and more political contacts as steps toward increased regional collaboration.

Education is also important, they said. Central Asian unity is the ideal, noted Burikhan Nurmuhamedov, director of the Institute of National Research in Almaty, but the region has never made it a priority. It should be a priority, and among the young research and political specialists coming out of Kazakhstan’s universities with focuses on China, Russia and other countries should be bright young experts on Uzbekistan, for example, and on their own region. He also said that the attitudes of potential partner powers – Russia, Europe and the United States, for example – should be evaluated on how they view Central Asian unity, with the implication being that a region that wishes to unite should choose strong partners who support that goal.

The impact of superpowers on Central Asia was also tackled, as well as their different points of view. From head of the Russia and Eurasian Programme at the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London James Nixey came a sharp criticism of the young EAEU, which he called “economic nonsense,” saying so far the union had only hurt regional economies.

Nixey also noted what he called two important geopolitical themes: “a growing intolerance of regional inequalities, which will affect us all … and a loss of trust in governments all over the world.” He also cautioned against a “geopolitical unravelling whereby competition is turning into conflict.”

From the Russian side came an explanation of some of Russia’s pragmatic criticisms of Kazakhstan’s multivector foreign policy. Kazakhstan has wanted to have close relationships with many partners – but when its partners end up in conflict, Kazakhstan ends up suffering damage from multiple directions, noted Andrey Kazantsev, director of the Analytical Centre of Moscow State Institute of International Relations. Kazantsev also commented in his opening remarks and in response to questions that the issues that have led to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine do not exist in Central Asia, and are not applicable to discussions of the sovereignty of Central Asian states.

Maulen Ashimbayev, Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security of the Mazhilis of Kazakhstan’s Parliament, discussed the importance of reform in reaching any of Central Asia’s goals. The next five to seven years are crucial for implementing reform, he said, without which, “we’ll become failed states and a failed region.” Kazakhstan is pushing ahead with this through its Plan for the Nation and the recently announced 100 concrete steps, as well as draft legislation he called “breakthroughs.”

A press release issued by KazISS on the day of the conference said the event’s goal was to foster understanding of the global issues and international relations system that influence Central Asia.

“In the context of the changing geopolitical situation, understanding global and regional processes has become a key factor to solving complex political and economic problems. In this respect, there is a growing role for expert assessments in the analysis of threats and challenges,” the release said.

“Of course, the topic is extremely difficult; the region is difficult. … I think it is clear that the topics and issues from 20 years ago are still important,” said Regional Director of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation office in Central Asia Peer Teschendorf in his concluding remarks.

“I think today’s conference helped us at least clearly define the key moments,” said moderator Erlan Karin, director of KazISS.

The conference gathered experts from political and research institutions in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, China, Iran, the Kyrgyz Republic, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkey, the U.K., the U.S. and Uzbekistan.