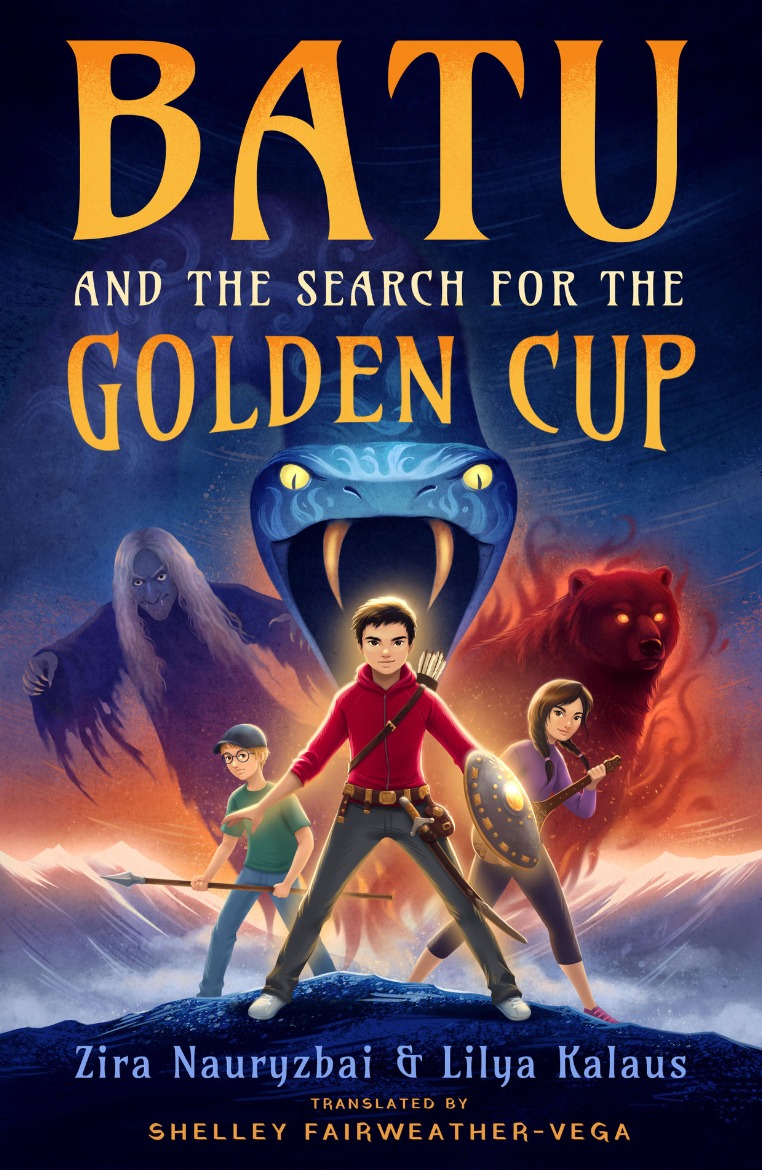

ASTANA – The children’s book series “The Adventures of Batu and His Friends” (2014, 2019, 2021) is a work of love for Zira Nauryzbai, a Kazakh mythology researcher, writer, and Ph.D. candidate in philosophical sciences, and for her co-author, Lilya Kalaus. This summer, the first book of the series entered the Amazon Crossing Kid’s bestseller list.

(from left to right) Co-authors of the book Lilya Kalaus and Zira Nauryzbai. Photo credit: personal archive of Nauryzbai.

Nauryzbai is a prolific author. Her galaxy of books includes monumental volumes, such as “The Kazakh’s Eternal Sky” (2013, 2020), “Four Clouds” (2017), “Female Images in the Mythology of the Pre-Kazakhs by Serikbol Kondybay” (2021), “Subject(s) of Kazakh Culture” (2022, co-authored with her late husband, Talasbek Asemkulov).

In an interview with The Astana Times, Nauryzbai discusses her journey, which began seventeen years ago when the writer’s children became obsessed with Pottermania (the craze around Harry Potter), and she embarked on an adventure no less thrilling than that of her book’s protagonist, Batu.

“We started this project 17 years ago. We initially wrote the first book as a comic and then as prose to pique our children’s interest in Kazakh mythology and culture, as well as of children who speak Russian,” said Nauryzbai.

A simple desire to arouse their children’s interest in Kazakh mythology and the Kazakh language led Nauryzbai and Kalaus to publish their first book in the series this summer on the Amazon platform in electronic form, bringing international recognition after the book entered the platform’s bestseller list several times.

After years of attempts, Marilyn Brigham, Editor at Amazon Crossing Kids, decided to introduce American and English-speaking children to Kazakh mythology. Photo credit: personal archive of Nauryzbai.

“I personally saw this project only as a way to ignite interest in Kazakh culture among Russian-speaking children. However, Lilya thought the book had strong potential in the global market. Shelley Fairweather-Vega, a translator from the United States, also played a key role in this story. In 2019, Shelley not only translated but also found the publishing company to release a novel by my late husband Talasbek Asemkulov,” said Nauryzbai.

She asked Fairweather-Vega to read the book and give her opinion on whether she sees any potential for it in the U.S.

“Shelley said the book was inspiring and there was a big chance it would succeed in the U.S. So Lilya and I asked her to translate one chapter of the book, the synopsis, and act as our literary agent,” Nauryzbai recalls.

Fairweather-Vega spent several years hunting for publishing companies, negotiating, and speaking at children’s literature conferences. There were initial signs of potential collaboration, but nothing came of it. After years of attempts, Marilyn Brigham, Editor at Amazon Crossing Kids, decided to shine a light on Batu and introduce American and English-speaking children to Kazakh mythology.

“It was quite exciting because the book took first place in one rating literally on the second day after its release, then it was in the lead in two others, and for three weeks the book was first among children’s books about Asia on Amazon,” Nauryzbai said.

With Amazon selling millions of titles, the book about a Kazakh boy’s adventures started at the 300,000th position on the Amazon ratings and has since risen to the top in several categories, eclipsing even Indian mythology, which is more well-known to Western audiences.

“This was unexpected for me. Although I understand that Amazon’s marketing department is putting in much effort to promote the book, I also see in the success the support of many of my supporters, including Kazakhs living here and abroad, who buy our book,” she said.

Worldwide cultural phenomena, like the Harry Potter novels and subsequent films, the Avatar movies, and the Japanese manga Naruto, inspired the writers.

The children’s book series “The Adventures of Batu and His Friends” (2014, 2019, 2021) were published in Russian at first. Photo credit: personal archive of Nauryzbai.

“It was obvious to me that many of these works made excellent use of the mythology of other cultures. Since I am an expert in Kazakh mythology, I also wanted to tell stories that incorporated Kazakh myths. Each of the trilogy’s novels features a unique myth. We began with the Kazakh myth about not standing or sitting in the doorway, as our protagonist Batu did at the beginning of the first book. His grandmother warned him not to do so. The Kazakhs believed that a threshold opened the door to another dimension. The first book also incorporated the myth of the first Scythian ruler, Kulaksai, who could gather golden items that were falling from the sky despite them being on fire. This ability allowed him to become a Scythian king. Herodotus also discussed the myth, and the Kazakhs have a riddle that relates to it,” Nauryzbai said.

She added that the authors incorporate the history of several regions of Kazakhstan into the plot alongside the myths and customs of the Kazakh people.

“Our heroes traveled to Semei and the nuclear test site in the first book, the Syr Darya and the Kyzylorda region in the second, and Kostanai and the Torgai area in the third. The places our protagonists go to and the people they meet have a strong connection to the region,” she said.

“We want Kazakh children to have a visual memory of their country, not only its name,” she noted.

Commenting about the differences she noticed while working with Western publishing organizations, Nauryzbai commended the publishers’ attentiveness, support, and positive attitude. However, there were a few hurdles due to a cultural clash over the book’s topic.

Nauryzbai galaxy of books includes “The Kazakh’s Eternal Sky” (2013, 2020), “Four Clouds” (2017), “Female Images in the Mythology of the Pre-Kazakhs by Serikbol Kondybay” (2021), “Subject(s) of Kazakh Culture” (2022, co-authored with her late husband, Talasbek Asemkulov). Photo credit: personal archive of Nauryzbai.

“We agreed in our contract to adapt the book for the American reader. When the book was finished, it was read by editors, proofreaders, and copyright specialists to ensure no plagiarism. One of the editors wanted to leave out an occurrence crucial to the book’s plot. It was about the character Zheztyrnak [copper nail], a witch in Kazakh mythology. In one of the book’s episodes, when Batu and his friends see her, they are scared of what she would do with a baby, but instead of killing it, she begins to nurse the infant. The editors wanted to delete this part from the book since such a subject is frowned upon in children’s literature in the U.S. They have an odd attitude toward breastfeeding. I am not sure why. I am not an expert, it is not for me to judge, but it was imperative to keep it because it is an essential part of the plot. I submitted several examples that explained the holiness of milk and dairy products in Turkic-Mongolian culture. Shelley, our translator, was able to defend the episode, and we managed to keep it in the book with only a small amendment to the phrasing. They omitted the word ‘breast’ from the sentence, editing it as ‘Zhestyrnak feeds the baby’,” Nauryzbai said.

Apart from this minor misunderstanding, Zira Nauryzbai said the book was translated accurately. The translator and editors of Amazon Publishing even kept a dictionary of ethnocultural terms that appear in the plot.

“Because we wrote this book with Kazakh youngsters and Russian-speaking Kazakh citizens in mind, we included a glossary of ethnocultural phrases used throughout the story. This contributed much to the book’s success in promoting a more positive image of the Kazakh language among young readers. There was no such challenge to pique the interest of a reader from the U.S. in the Kazakh language. Access to the global market and the fact that they are aware of Kazakhstan and its unique culture were sufficient for us,” she said.

When discussing the differences between traditional Kazakh and post-Soviet or even modern upbringing in a typical Kazakh family, Nauryzbai remarked that traditional Kazakh families were conscientious about the words they used around children.

“I remember the words of my nagashy azhe [grandmother from the maternal side]. She scolded us when we misbehaved with the words ‘Bar bol! Orkenin ossin,’ which roughly translates as ‘Be well! May all your endeavors find success!’ These were the words she used when she truly wanted us to behave. We knew these were the worst words she used when she was strict with us, but it was odd that she used blessings instead of curses to get us to behave. When we asked why she scolded us while using kind words, she responded, ‘Why should I call you bad words?’” Nauryzbai said.

But not all grandmothers were like this. Nauryzbai recalls childhood visits to relatives in villages, where other grandparents reprimanded their grandkids harshly.

“As a child, I could tell the difference between traditional and Soviet upbringing. When the Kazakhs scolded their children, it was always a blessing. They spoke very cautiously and tenderly in front of the children. They did not swear. Unpleasant and negative topics were never discussed, especially in front of a young woman and a pregnant daughter-in-law,” Nauryzbai added.

Addressing foreign audiences’ misconceptions about the Kazakh people, Nauryzbai stated that the term “nomad” in the understanding of foreign audiences does not accurately convey the Kazakh civilization, lifestyle, and life in the steppe. Many people associate nomads with European gypsies.

“The debate has been going on for a long time, since the 1990s, and even Kazakh authors have written that the word koshpendi [nomad] is inaccurate in Kazakh, that there is a word koshpeni [a similar meaning to nomad]. However, even in these circumstances, the nuances must be considered, even though both words, in my opinion, are artificially produced terms. The term nomad comes from the Latin ‘nomas’ [wandering shepherd], and it means a nomad who roams chaotically,” Nauryzbai said.

In that sense, the Kazakhs were not nomads. According to Nauryzbai, the Kazakhs regarded themselves as rulers of their territory. They formed their lifestyles closely with nature, moving about the country based on natural phenomena and following centuries-old routes.

“Of course, the Kazakhs followed the routes established over ages on their territory. Nomadologists noted in the 1960s and 1970s that these are two distinct things: seasonal migrations of Kazakhs and other similar peoples linked to certain natural circumstances along specific routes. When people were forced to flee their homeland due to catastrophic events, climate change, or enemy defeats, they had to leave their historical territories in search of new land as the Hungarians or Bulgarians, led by Khan Asparuh, were forced to leave and acquire their new homeland in Bulgaria. These are two distinct things. We should seriously consider not using the term ‘nomad’ as a description because it does not adequately express the meaning of our civilization,” Nauryzbai concluded.