ASTANA – Kazakh women’s history museums educate and empower women, providing an awareness-raising platform and tools for overcoming discrimination, said Women of Kazakhstan founder Dinara Assanova in an interview with The Astana Times.

Assanova’s family provided her with a keen awareness of women’s contributions to society from a young age.

“Motivation to study Kazakh women’s history was given to me by my grandfather,” she said. “He was the one to initiate his private collection of outstanding women in Kazakhstan that I inherited.”

That private collection has since been expanded into a structured and thoroughly researched public one, with followers making their own submissions about their mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers. The non-governmental organisation Women of Kazakhstan runs the country’s first virtual museum on its Instagram (@womenofkz), also publishing Kazakh women’s photographs, biographies, folklore legends, poems and paintings on Facebook and Twitter (@womenofkz). Museum exhibitions have featured Kazakh names, toponyms, mythology, phaleristics collections, philately and numismatics. Assanova hopes to also develop a physical museum, library, research centre and database.

“We have a great exhibition based on the research of Adrienne Mayor, historian of Stanford University, on the female eagle hunting traditions in Kazakhstan. Another photography exhibition is based on our unique research on the streets of Almaty named after women,” she noted.

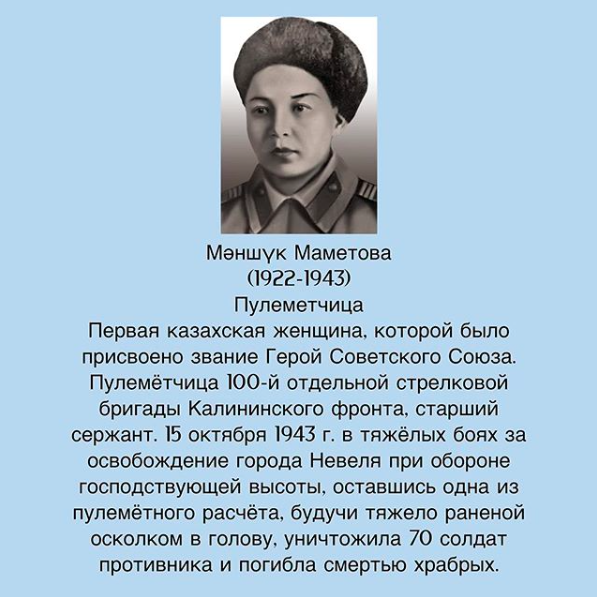

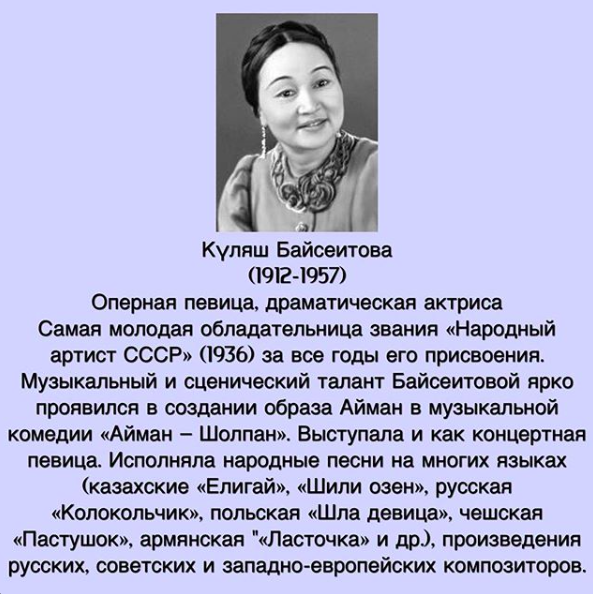

Scholarship on women’s role in history has expanded in recent years, challenging and widening the traditional consensus on history. Kazakh history textbooks now feature Manshuk Mametova, one of two Kazakh women to be awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union title for her bravery during the Second World War, and Kulyash Baiseitova, the youngest to be awarded a People’s Artist of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics title for her opera singing.

“Knowledge of women’s contributions is a great tool of inspiration and empowerment,” said Assanova. “Legacy matters. For every Manshuk Mametova and Kulyash Baiseitova, there are thousands of women who deserve to be part of the historical narrative of our country… Gaukhar Zakumbayeva developed unique catalysts for oil refining, which allowed for increasing the depth of oil refinement from the usual 50-60 percent to 95 percent; Sofiya Takibayeva restored the most sophisticated bricks, majolica, terracotta and glaze for the Mausoleum of Khoja Akhmed Yassawi; former Minister of Culture Laila Galimzhanova made a huge contribution to the development of cinematography in our country and recently, artists Saule Suleimenova and her daughter Suinbike Suleimenova unveiled the story of Lydia Blinova, artist and wife of the famous painter Rustam Halfin.”

Today, there are women’s museums on every continent.

“There are about 300 women’s museums in the world – all of them are united by the desire to build a collective image of women’s culture and history, which was never specifically collected, preserved or studied,” she noted, adding Women of Kazakhstan joined the International Association of Women’s Museums in 2018.

Museums allow visitors to place their identity within historical and cultural contexts, but have not always been socially and economically inclusive spaces. In integrating technology into the exhibitions, the organisation hopes to bring the museum to the people, rather than vice versa.

“There are no [other] virtual museums in Kazakhstan,” she said. “When most of the archival material is online, it is easily accessible. One can always find material there to work on an article, post, abstract or research, so [physical] visits to archives and museums can be significantly reduced.”

Parts of the country’s economy, government and human capital development are undergoing digitisation as part of the Digital Kazakhstan state programme. Assanova hopes to see Kazakhstan’s scientific works, archival photographs and audio-visual material in its 234 museums as accessible online as material from the United States Library of Congress and Louvre Museum Internet archives.

“Throughout the world, museums are turning into spaces that are reviving the cult of knowledge; with the help of the internet and good content, this is possible. With the advent of the internet, our life has ceased to be the same, so we need to change the paradigms of museum work in Kazakhstan,” she noted, pointing to Almaty’s Abilkhan Kasteyev State Museum of Arts’ use of social media in promoting local art.

“The only photographs of Kazakh women that have been professionally restored and colourised in a digital format are three photos of Khiuaz Dospanova,” she added, referring to photo colourist Olga Shirnina’s restorations of the Kazakh pilot. “I am really looking forward to creative enthusiasts in Kazakhstan who will restore photographs of Kazakh history, which would allow us to see the past in a completely different light.”

Assanova leads by example in making museums more accessible by allowing visitors to take photographs and videos of the exhibitions.

“It will be much easier for people to study history when they can imprint a pattern from a sholpy [Kazakh jewelry] from the 19th century and capture a picture of the only Kazakh nurse to have received the highest international medal, the Florence Nightingale Medal!” she said.

She noted among Kazakhstan’s numerous and diverse organisations working on women’s rights, many lack historical information to advance their cause.

“I think that what I do serves women’s interests, women’s history and women’s movements,” she added. “I want our women to know their history and be proud and inspired by their predecessors. I am confident that the education and professional development of a woman will help all of us grow into a highly intelligent generation that will turn Kazakhstan into a country with a high level of human development.”