ALMATY – A public lecture in Almaty on Jan. 24 explored how ancient petroglyphs in Kazakhstan may reflect early astronomical knowledge, tracing humanity’s understanding of the night sky from prehistoric times to modern science.

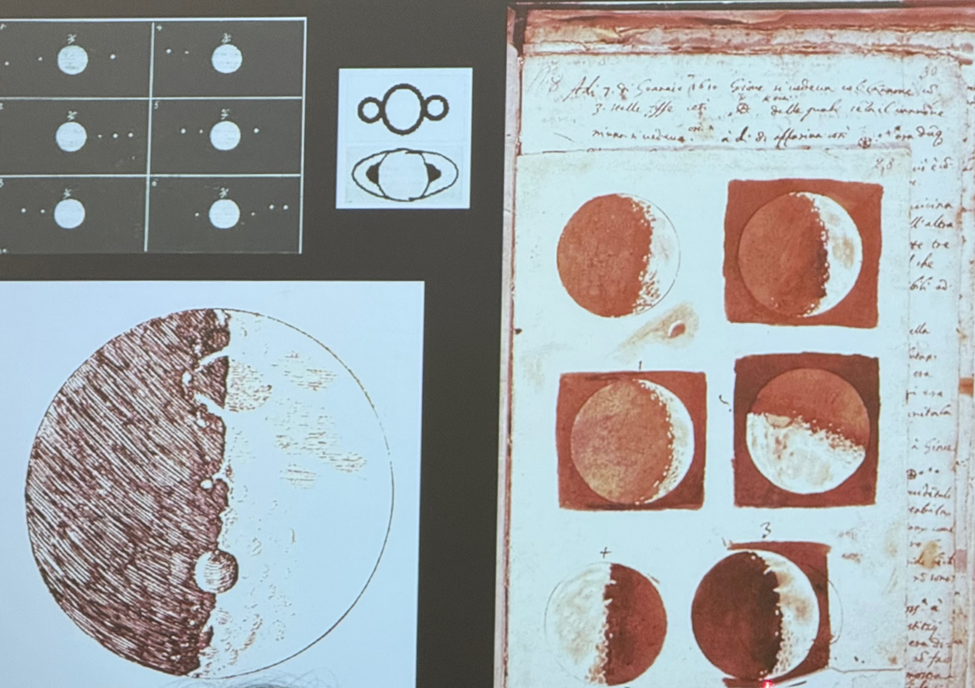

Sketches from the 17th century, illustrating early telescopic observations of Saturn, Jupiter and the Moon. Photo credit: The Astana Times.

In his talk, Denis Paryshev, a science communicator, astrophotographer and organizer of the Petroglyph Hunters expeditions, connected archaeological findings with the evolution of astronomical observation, suggesting that early steppe cultures closely monitored celestial cycles and incorporated them into daily life, rituals and timekeeping.

Denis Paryshev presented the history of petroglyphs and their connection with the early astronomy. Photo credit: The Astana Times.

Paryshev outlined how humans began observing the sky in the Paleolithic era and gradually developed systems to interpret celestial patterns. Particular attention was given to symbols and structures found across Kazakhstan, including kurgans with moustaches (burial mounds with stone ridges), balbals (stone markers), and references to the Pleiades star cluster.

According to Paryshev, kurgans may have served as ancient calendrical markers. Two curved stone ridges extending southward from the mound align with the points of sunrise during key solar events such as solstices and equinoxes.

“The sunrise point was observed on one of the moustaches of the mound, and the sunset point on the other,” Paryshev said.

The pleiades, he added, played an important role in traditional forecasting.

“There were people who observed the sky and compared it with natural phenomena. If the constellation of the pleiades appeared, it meant it was going to be cold soon. Conversely, when it set, it meant it was going to be warm,” Paryshev said.

The lecture also discussed how celestial phenomena could have been perceived by ancient people and influenced their religious views and rituals.

“What was fascinating about the sky and space was the image of birds, which were rarely depicted. When they did appear, it was usually in connection with altars, most often represented by a stone. People would offer prayers at these altars and leave food as offerings. Birds would fly down, eat the food, and then fly away. It was believed that the prayers, carried off with the offerings, were delivered directly to Tengri,” Paryshev said.

Bridging past and present, Paryshev concluded by discussing modern astronomical research, including gravitational-wave observatories such as LIGO, VIRGO and the planned space-based LISA mission. He described how these facilities detect ripples in space-time by measuring tiny changes in the length of laser beams traveling between mirrors.

As part of the lecture, the public also asked questions ranging from melting comets and black holes to dark matter and galaxy formation, underscoring continued interest in both ancient and modern views of the universe.